Read Part 1 first!

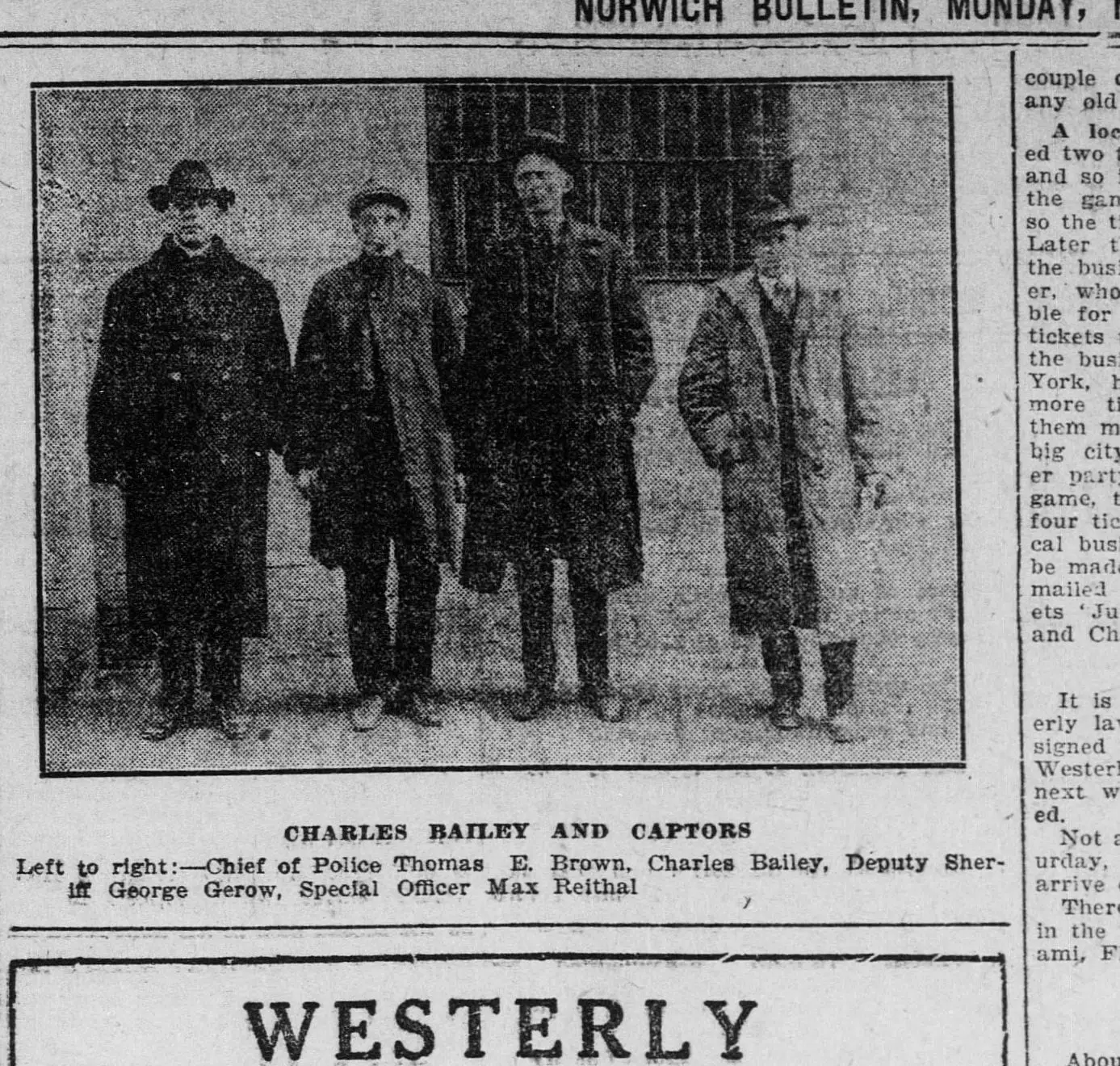

On Friday, November 5, Police Chief Brown and Constable Max Reithel departed for Maine in search of their fugitive.[23] By Sunday afternoon, the officers had a strong lead on Bailey. After unsuccessfully searching for their man at local stables due in large part to his reputation as a horse trader, the Westerly officers inquired with the local police.[24] At 3 p.m., Brown and Rerthol, along with Yarmouth (Maine) Deputy Sherriff George W. Gerow, located Bailey at a boarding house in Bowdoinham.[25]

Upon seeing the officers approach the boarding house, Bailey took off towards the nearby woods. As their man tried to make a getaway, the officers fired in Bailey’s direction, causing him to surrender.[26] After giving himself up to the police, Charles Bailey was held overnight in jail in Portland, Maine and the following morning, he departed with the officers for Westerly.[27]

On the morning of Monday, November 8, Charles E. Bailey returned to Westerly in police custody where he was temporarily held while awaiting trial. The following morning, he was brought to the Third District Court in Kingston where he plead not guilty to the charge of murder.[28] On Friday November 12, Bailey returned to the court for a preliminary hearing, at which time he claimed he had no money to pay for an attorney. The defendant was then reminded that he had $143 ($1,850 in 2020) in his possession at the time of his arrest. Bailey countered this claim by stating the money was owed to his mother, although she denied that was the case.[29] Bailey was eventually assigned A.T.L. Ledwidge as his attorney.[30] The hearing was adjourned and it was proclaimed that the trial would begin at the Superior Court of Washington County in Westerly the following Monday.

Although Bailey never denied shooting his brother, he did consistently maintain that the shooting was accidental, hence his plea of not guilty to the charge of murder. Julia, the matriarch of the Bailey family, and the only other living witness to the incident, was also steadfast in her belief that the shooting was unintentional.[31] Another witness, John J. Gilcrist, was called to testify during the trial. Gilcrist claimed that prior to the shooting, he had been with Charles who had “a couple glasses of cider” on their trip into the country.[32] Gilchrist also revealed that after the shooting, Charles came to his house and said he had something to tell him, however, Gilchrist did not listen, closed the door, and went to bed.[33]

According to the statement given by the accused to Chief Brown, Bailey was holding the revolver that he intended to take “into the country to trade off” when he started clicking the revolver which inadvertently fired.[34] Chief Brown also testified that Charles told him “Edgar acted as if he did not want [him] around the house and [he] did all the chores. He never felt a [sic] Welcome at home.”[35] This statement was particularly important, as it established a possible motive, which had been lacking up to that point.

After hearing from the Westerly Police Chief, Charles Bailey was brought to the stand to testify. According to Bailey, he purchased the revolver about two years prior from a man named Will Whitmore who lived on Wells Street in Westerly. At the time of the purchase, there were three cartridges in the revolver. Whitmore fired one of the cartridges while Bailey fired the other and Bailey testified that the third cartridge had remained in the gun unused for so long that he had forgotten about it.[36] Bailey further claimed he had never purchased any shells for the gun and none were ever given to him. When asked about the incident, Bailey testified that there was no trouble in the house that evening and there were no problematic discussions.[37] Bailey also told of his journey to Maine and indicated that he did not communicate with anyone while in Westerly after the shooting and he told no one of the incident while in Maine.[38]

The trial took place over the course of two days between November 29-30, 1920 and the overall time from opening statements to the start of jury deliberation was seven hours and thirty minutes.[39] After just over three hours of discussion and consideration, the jury declared Bailey guilty of manslaughter.[40] The first ballot delivered by the 12 members of the jury revealed that seven jurors supported a guilty verdict while the remaining five favored an acquittal.[41] In order to provide more context, the jurors had been taken to the scene of the murder.[42] Over the course of the two-day trial, the jurors were required to stay together and were put in the custody of the sheriff to ensure this. Several months after being declared guilty, Bailey was sentenced to 12 years in prison.[43]

Bailey served his sentence at the Rhode Island State Prison in Cranston where he was recorded in 1925.[44] Once again, Charles Bailey disappears from records for several years, so it is unclear if he served all 12 years of his sentence. It is known that by 1939, he had returned to Westerly, where he lived on the town farm off of Bradford Road.[45] In 1940, Bailey was recorded as an inmate on the town farm, but it is uncertain as to whether he was simply living on the farm or serving another sentence.[46] On January 29, 1942, Charles Bailey died on the Westerly Town Farm where he had been working as a gardener.[47] Bailey left no surviving family, and although he was interred in River Bend Cemetery, he was not buried with his mother and brother. For a brief period at the end of 1920, the actions of Charles E. Bailey led to the one of the few murder trials in Westerly’s long history.

[su_accordion class=””] [su_spoiler title=”Footnotes” open=”no” style=”default” icon=”plus” anchor=”” class=””]

[23] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 9 November 1920.

[24] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 10 November 1920.

[25] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 10 November 1920.

[26] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 9 November 1920.

[27] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 10 November 1920.

[28] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 17 November 1920.

[29] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 17 November 1920.

[30] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 22 November 1920.

[31] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[32] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[33] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[34] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[35] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[36] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[37] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[38] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[39] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[40] “Charles Bailey of Westerly Guilty of Manslaughter” Norwich Bulletin, 1 December 1920.

[41] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 6 December 1920.

[42] “Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 30 November 1920.

[43] “New England News in Tabloid Form” Oxford Democrat, 3 May 1921.

[44] Rhode Island State Prison, Cranston, Providence, Rhode Island, 1925 Rhode Island Census, Enumeration District 96, pg. 20.

[45] U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, Westerly, Rhode Island, 1939, pg. 109.

[46] Household of Arthur C. Maine, Westerly, Washington, Rhode Island, 1940 United States Census, Roll: m-t0627-03772; Page: 8B; Enumeration District: 5-31.

[47] Rhode Island Department of Public Health, Certificate of Death, Charles Bailey, City No. 42-14, State File No. 12.

[/su_spoiler] [/su_accordion]