Being a genealogist by trade and having spent countless hours pouring over records for thousands of my ancestors, I thought I knew everything I could possibly learn about many of my ancestors, especially ones as recent as four generations ago. For this reason, I was surprised to learn of a series of incidents involving my great2 grandparents that led me to uncover a fascinating story from Westerly’s past.

Natale Bonvenuto, my great2 grandfather, was born in Acri, Calabria, Italy on December 11, 1864, the son of Angelo Bonvenuto, a farmer, and his wife, Teresa (Morrone) Bonvenuto. [1] On March 1, 1889, he arrived from Calabria at the port of New York and made his way to Rhode Island.[2] Little is known about his early life in America, but he is presumed to have arrived in Westerly by 1895, because it was in this year that he married Christina Falcone, who had herself been born in Acri and arrived in America on December 8, 1894.[3]

For several years after arriving in the United States, Natale worked as a general laborer, most often finding himself as a quarryman, like so many of his fellow Italian immigrants. After more than a decade of employment in the granite quarries, Natale sought a different way to support his wife and four children. However, his initial attempts at moneymaking found him on the wrong side of justice.

On January 15, Natale and Christina found themselves before the Third District Court, having been charged with keeping liquor with intent to sell. They both plead nolo contendre, accepting the conviction without admitting guilt. Christina, being the mother of three children including a two-year-old, had her case suspended for three months and was placed on probation.

Natale, however, contended that his wife was the only one who had violated the law, as she was the only one to have sold liquor that evening.[6] Despite his questionable defense, the judge imposed the full penalty, ten days in jail plus a $20 fine, upon Natale. Natale pleaded to have the jail term withheld in exchange for a higher fine, but the court was bound by statute and had no say in the sentence.[7]

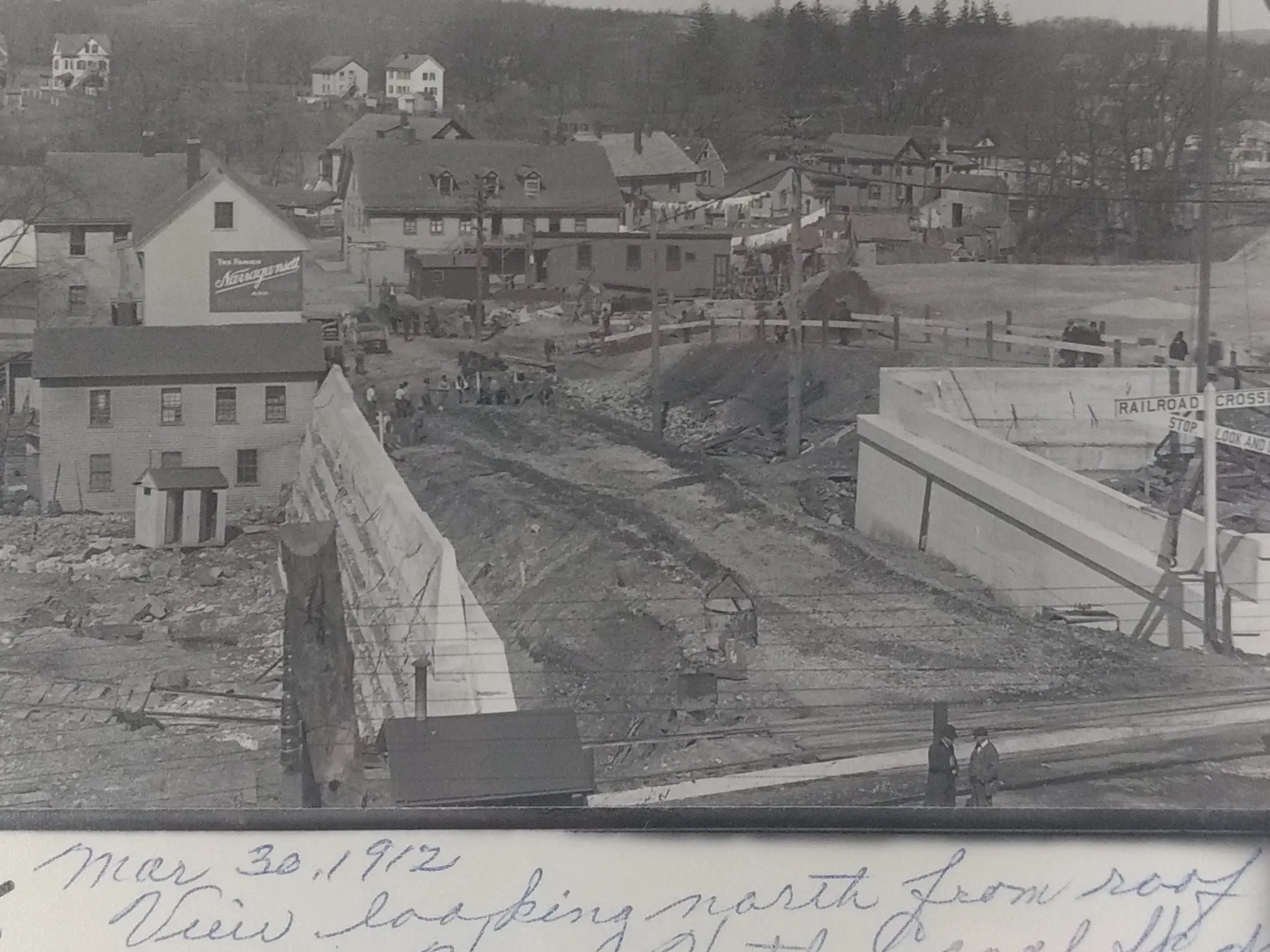

Natale and Christina remained in the good graces of local law enforcement after their initial troubles. In March 1911, a man by the name of John Carney petitioned to transfer the liquor license from his Canal Street bar to Natale.[8] At some point before February 1912, Natale was granted the transfer of license. Unfortunately, the location of the saloon was in the path of planned expansions being undertaken by the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad, and at the request of the railroad, he moved the building onto a piece of land on the opposite side of Canal Street.[9]

When the building was relocated, the land where it was moved to was believed to be owned entirely by the railroad. This belief was challenged by Concertino Grills who owned the land directly next to the saloon. Grills claimed that the saloon was located partly on his property and brought a lawsuit against both the railroad and Natale Bonvenuto. Lawyers for Grills argued that the improper location of the saloon made the liquor license invalid.[10]

In February of 1912, with a lawsuit underway, Grills constructed a fence blocking the main entrance to the saloon. Patrons could still enter the building through the rear, but it was ruled that the fence had to be removed.[11] Although the license to sell liquor was challenged by lawyers for Grills, health officers chose not to order the saloon closed.[12]

At that time, the court also ruled that Natale could continue to operate his saloon at the same location until the title of ownership was determined.[13] There would be many more claims in this case which would continue on for several more years. In the meantime, however, Natale continued to operate his saloon, which had since come to be known as the Tin Tub.

While the legal battles over the ownership of the Canal Street property continued on, Natale Bonvenuto faced more immediate problems for his business. On April 4, 1913, an unknown assailant set off a stick of dynamite under the saloon building at midnight. Thankfully, no damage resulted from the attempt aside from a small trash fire. Upon seeing the small blaze, the fire department was called in, but little effort was required to extinguish it.[14] Detectives were unsuccessful at finding the culprit and Natale offered a $50 reward for discovering the attacker(s). This attempt at destroying the saloon would be the first of several over the following months.

Less than two weeks later, early in the morning on April 17, 1913, Engineer Walter Pendleton at the Westerly Light and Power Company’s plant sent in a fire alarm when he found the rear end of the Tin Tub Saloon ablaze.[15] According to one account of the fire, the flames had “burned through the floor and inside, [the saloon’s] contents were badly burned and blistered as a result of the excessive heat. Some of the bottles that were behind the bar burst and a number of barrels of liquor in the basement were destroyed. The stock and fixtures were damaged beyond repair, but the bar can be repaired at considerable expense, however.”

The article noted that insurance would partly cover the losses.[16] When investigators entered the building after the fire had been extinguished, they found evidence that kerosene had been spread on the floor, indicating that the fire was likely set intentionally. The newspaper coverage of the fire described Natale as “a quiet, peaceable man” and stated that he was “at a loss to know why the guilty party or parties are committing such outrages upon his property.”[17]

As if the damage caused by the fire was not enough, on August 8, 1913, a second attempt was made to blow the saloon up with dynamite.[18] This marked the third time overall since April of that year that someone had attempted to destroy the building. For the first time, a possible motive for the crimes was presented. According to the Westerly Sun: “The police believe that these attempts at destruction are prompted by jealousy, as Benvenuti [sic] seems to be doing profitable business in his little place, while more pretentious saloons are hardly able to meet expenses.”[19]

Still, Natale persisted with his business, as he was granted a new liquor license in November 1913. That same month, another saloon was attacked. This time, the culprit, possibly the same as from the prior incidents, attempted to dynamite an establishment owned by Joseph S. Grills, the same man who challenged Natale’s land rights in court.[20] As with the crimes against Natale’s saloon, a culprit was not immediately identified.

Trouble continued to find its way to the Tin Tub Saloon throughout the following years. On February 10, 1914, a man by the name of Pasquale Salameno, a former police officer, shot a patron, Charles Brown, at the saloon. Brown survived the shooting and Salameno faced charges of assault with intent to kill and carrying a concealed weapon.[21] Brown was wearing a coat, a sweater, a vest, and two shirts, and as a result, the bullet did not penetrate all of the clothing and he was uninjured.[22]

In April 1914, the Rhode Island Supreme Court heard the case of Grills vs. the NYNHH Railroad and Natale Bonvenuto. Ultimately, the court decided in favor of Grills and determined that “the building must be removed or mutual arrangement made to the contrary.”[23] The court cases continued on through the following year, as Natale brought a suit against Joseph S. Grills at the Westerly Superior Court in May 1915.[24]

On Independence Day 1915, the Tin Tub Saloon once again escaped serious harm when the building next to it (described by the Westerly Sun as being within three feet) was destroyed in a fire. Despite the close proximity of the saloon to the burning building, Natale’s saloon suffered only a scorched wall facing the burnt building.[25]

As for the court cases Natale was involved in, it appears as though they were quietly resolved. In November 1915, the case against Joseph S. Grills was assigned for trial in Westerly.[26] On December 2, 1915, Judge John W. Sweeney of the Rhode Island Superior Court was a witness in the case, as he was Natale’s attorney before being named a judge. This is the last known reference to the case made in local newspapers, suggesting that the case was likely resolved and was not challenged further.

In November 1916, Natale was denied a liquor license, marking the end of his career as a saloon owner.[27] By 1917, he was once again recorded as a laborer, suggesting he likely returned to his career as a quarryman.[28] Meanwhile, Joseph S. Grills, who had begun operating a saloon on Canal Street some years earlier, continued running his bar for several years after the Tin Tub closed.

Natale Bonvenuto died in Westerly on January 7, 1927 at the age of 62.[29] It is unlikely that he ever discovered the perpetrator who attempted to destroy his business on multiple occasions, as there does not seem to have been a resolution to the investigation. Despite several attempts to take away his livelihood, my great grandfather, Natale Bonvenuto, persisted, continuing to operate his saloon in the face of danger.

[su_accordion class=””] [su_spoiler title=”Footnotes” open=”no” style=”default” icon=”plus” anchor=”” class=””]

1) Acri, Calabria, Atto di Nascita, Num. d’ordine 373, Folio 187, 11 December 1864.

2) Naturalization, Supreme Court of Washington County, Rhode Island, 14 July 1902.

3) Rhode Island Public Health Commission, Certificate of Death, No. 78, Christina Bonvenuto, June 9, 1941 and Customs List of Passengers, District of the City of New York, RMS Campania, 8 December 1894.

4) “Not Santa Claus” Westerly Sun, December 1908.

5) “There was beer flowing down the gutters….” Norwich Bulletin, 15 January 1909.

6) “Natale Benvenuti attempted the Adam and Eve act…” Norwich Bulletin, 16 January 1909.

7) “Natale Benvenuti attempted the Adam and Eve act…” Norwich Bulletin, 16 January 1909.

8) “There is certainly a muddle over the status….” Norwich Bulletin, 25 March 1911.

9) “The disputed ownership…” Norwich Bulletin, 13 February 1912.

10) “The disputed ownership…” Norwich Bulletin, 13 February 1912.

11) “The disputed ownership…” Norwich Bulletin, 13 February 1912.

12) “There was a special meeting of the Westerly town council” Norwich Bulletin, 15 February 1912.

13) “There was a special meeting of the Westerly town council” Norwich Bulletin, 15 February 1912.

14) “Local Laconics” Norwich Bulletin, 7 April 1913.

15) “Kerosene in Westerly Saloon” Norwich Bulletin, 18 April 1913.

16) “Kerosene in Westerly Saloon” Norwich Bulletin, 18 April 1913.

17) “Kerosene in Westerly Saloon” Norwich Bulletin, 18 April 1913.

18) “The Little Wooden Building” Norwich Bulletin, 14 August 1913 and “Wrecked at Last” Westerly Sun, August 1913.

19) “The Little Wooden Building” Norwich Bulletin, 14 August 1913.

20) “The dynamiters who have made…” Norwich Bulletin, 3 November 1913.

21) “In the Superior Court….” Norwich Bulletin, 21 April 1914.

22) Norwich Bulletin, 12 February 1914.

23) “What is Interesting in Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 10 June 1914.

24) “Cases in Westerly Superior Court” Norwich Bulletin, 18 May 1915.

25) “Current Topics in Westerly” Norwich Bulletin, 18 May 1915.

26) Norwich Bulletin, 16 November 1915.

27) “Last Tuesday…” 14 November 1916.

28) 1917 Westerly Directory.

29) Return of a Death, State of Rhode Island, Natale Bonvenuto, 7 January 1927.

[/su_spoiler] [/su_accordion]