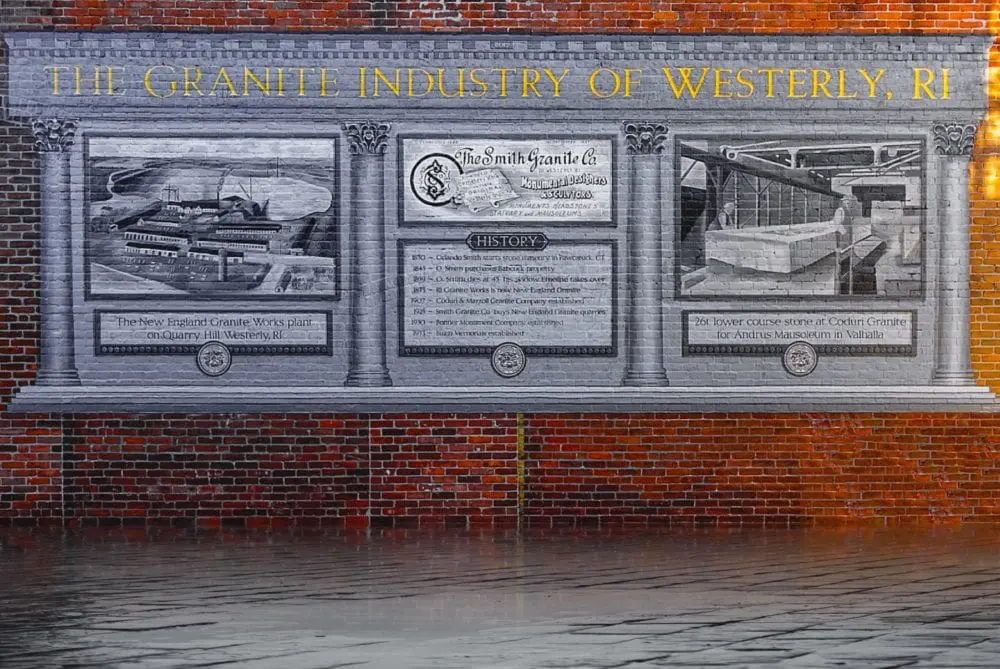

The following is part nine in Westerly Life’s “Behind the Murals” series discussing the history behind all of the recently created murals throughout downtown Westerly and Pawcatuck. The mural discussed below, which presents a look at Westerly’s history in the granite industry, can be found between Shield Martial Arts and Fret’s Guitar Workshop.

If there is any one industry that has been inextricably connected to Westerly’s history over the last two centuries, it is the granite industry. While the granite industry had far-reaching implications for the town which continue to this day, it has also brought the community into the national spotlight.

The history of the granite business as a major player in Westerly’s economy can be traced back to 1845, when Orlando Smith found a significant deposit of granite on a piece of farmland owned by the Babcock family. The following year, he purchased the land and began extracting its valuable granite.[1]

Although the first granite in Westerly was excavated eleven years prior in 1834, it was Smith’s discovery that led to a boom in business which would continue for decades.[2] From the 1830’s until the end of World War I, the industry thrived in Westerly.

While there were a number of reasons for the industry’s success, there were several important factors which combined to create an ideal environment for growth. The late nineteenth century saw an increase in ‘garden-like’ cemeteries which featured elaborate monuments which required skilled granite carvers.

Additionally, granite companies filled the demand for monuments and memorials at the end of the Civil War. Lastly, the granite found in Westerly was ideal for delicate and detailed work which these monuments necessitated.[3]

Expansion in the granite business meant a greater need for laborers in quarries throughout Westerly. As a result, the community saw a massive uptick in the number of migrant workers. The first group to arrive and find work in the quarries were the Irish in the 1850’s, followed by Scots in the 1870’s.[4]

By 1885, eighteen percent of Westerly residents were Irish-born, while ten percent were born in Scotland. The influx of Scottish immigrants in Westerly was due largely to a crowded job market for granite workers in their native country.[5]

One company, Joseph Newall and Co., was a branch of the D.H. and J. Newall Company of Dalbeattie, Scotland, which formed in 1820, and linked the Scottish industry across the Atlantic Ocean.[6] Finns began arriving in droves in the 1890’s.[7] The group that arrived in the greatest numbers, however, were the southern Italians. The Italian immigrants who made Westerly their home have left an enduring legacy, with many of their descendants still calling Westerly home.[8]

By 1892, more than half of the town’s 7,000 citizens were “in some way tied to the economic well-being of the granite industry in Westerly.”[9] Granite’s impact on Westerly and the sheer volume of the industry’s output continued to grow throughout the nineteenth century. In an 1897 directory, there were 25 granite companies listed as operating in Westerly. The second highest was Providence with only six.[10]

Despite the high number of granite companies in Westerly at the time, it was clear that there were some which were viewed as major players. One such company was the New England Granite Works, which began operating a quarry known as the Rhode Island Granite Works, in 1868.[11]

The most notable company in town, however, was the one founded by Orlando Smith, known as the Smith Granite Company, which opened in 1846 with his purchase of the Babcock farm. Between 1880 and 1898, the company had sales offices in cities throughout the country, including New York, Chicago, Boston, Cleveland, and Philadelphia and maintained a staff of four hundred employees.[12]

The industry continued to thrive in the early decades of the twentieth century, however, by the time the Great Depression struck the nation in 1929, the granite business was beginning to wane.[13] Many of the smaller companies across town sold their quarries to larger firms and up-start enterprises.

Also leading to the industry’s downfall was a series of labor disputes, with an extended strike in 1922 affecting the industry deeply.[14] By the start of World War II, most granite companies had closed their doors, however, a few remain in operation to this day, albeit on a much smaller scale than during the industry’s peak.

Several notable monuments and buildings were carved in Westerly or were created using granite which was extracted from quarries in town. This includes the famed private soldier monument standing at the Antietam battlefield.

This monument, which stands over 44 feet tall and weighs 250 tons, was also displayed at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and was formally dedicated on September 17, 1880.[15] Altogether, more than one hundred Civil War monuments were created in Westerly between 1880 and 1900.[16]

Due in large part to the dedicated work of the researchers at the Babcock Smith House in Westerly (authors of the comprehensive and fascinating work Built from Stone), it has been found that the Smith Granite Company created at least 3,754 monuments standing in 32 states across America.[17]

Several well-known buildings in Westerly were also built using local granite, including the Watch Hill Lighthouse, Saint Pius X Church, the Town Hall, the Industrial Trust Company Building, and the Christopher Columbus monument in Wilcox Park.[18] The wide-reaching impact of Westerly’s granite industry is apparent not only in the number of monuments which can still be seen today but also through its shaping of the town’s history.

[su_accordion class=””] [su_spoiler title=”Footnotes” open=”no” style=”default” icon=”plus” anchor=”” class=””]

[1] Lementowicz, Anthony Jr., “Labor’s Eden: Worker Protest in Westerly Granite Quarries, 1870-1910” (1997).

[2] Lementowicz, Anthony Jr., “Labor’s Eden: Worker Protest in Westerly Granite Quarries, 1870-1910” (1997).

[3] The Babcock Smith House Museum, “The Granite Connection” Pamphlet.

[4] The Babcock Smith House Museum, “The Granite Connection” Pamphlet.

[5] Lementowicz, Anthony Jr., “Labor’s Eden: Worker Protest in Westerly Granite Quarries, 1870-1910” (1997).

[6] Brayley, Arthur Wellington, History of the Granite Industry of New England, (Boston, MA, 1913), pg. 165.

[7] The Babcock Smith House Museum, “The Granite Connection” Pamphlet.

[8] Lementowicz, Anthony Jr., “Labor’s Eden: Worker Protest in Westerly Granite Quarries, 1870-1910” (1997).

[9] Lementowicz, Anthony Jr., “Labor’s Eden: Worker Protest in Westerly Granite Quarries, 1870-1910” (1997).

[10] Mine and Quarry News Bureau, The Mine, Quarry, and Metallurgical Record of the United States, Canada, and Mexico: Containing Carefully Prepared and Revised Lists of Companies and Individuals Engaged In and Information Regarding the Mining and Quarrying and Kindred and Dependent Industries of North America. Together with the Mining Codes of the United States, Canada and Mexico, and Digests of the Commercial, Corporation and Mining Laws of the States, Territories and Provinces of the United States and Canada, (Chicago, IL, 1897).

[11] Dale, T. Nelson, United States Geological Survey, “The Chief Commercial Granites of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island” (1908), pg. 196-197.

[12] The Babcock Smith House Museum, “The Granite Connection” Pamphlet.

[13] The Babcock Smith House Museum, “The Granite Connection” Pamphlet.

[14] Chaffee, Linda Smith and John B. Coduri and Ellen L. Madison, Built from Stone: The Westerly Granite Story, (Westerly, RI, 2011).

[15] The Babcock Smith House Museum, “Westerly Granite at Antietam” Pamphlet.

[16] Chaffee, Linda Smith and John B. Coduri and Ellen L. Madison, Built from Stone: The Westerly Granite Story, (Westerly, RI, 2011).

[17] The Babcock Smith House Museum, “The Granite Connection” Pamphlet.

[18] Chaffee, Linda Smith and John B. Coduri and Ellen L. Madison, Built from Stone: The Westerly Granite Story, (Westerly, RI, 2011).

[/su_spoiler] [/su_accordion]