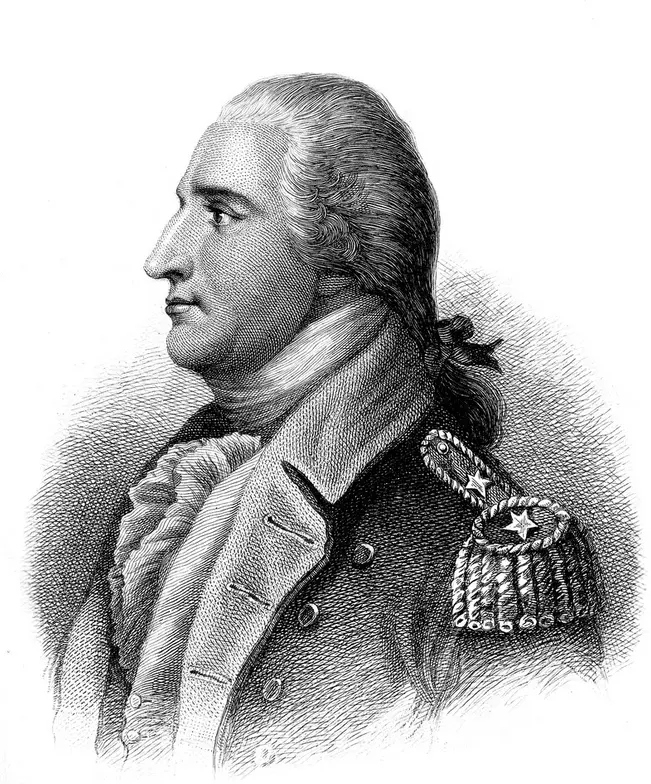

After the British withdrawal from Philadelphia in the spring of 1778, George Washington appointed Benedict Arnold the military commander of the city. Historian John Shy states, “Washington then made one of the worst decisions of his career, appointing Arnold as military governor of the rich, politically divided city. No one could have been less qualified for the position. Arnold had amply demonstrated his tendency to become embroiled in disputes, as well as his lack of political sense. Above all, he needed tact, patience, and fairness in dealing with people deeply marked by months of enemy occupation.”

Arnold lived extravagantly in Philadelphia and was a prominent figure on the social scene. During the summer of 1778, he met Peggy Shippen, the beautiful 18-year-old daughter of Judge Edward Shippen, a Loyalist sympathizer. They were married in April 1779. Arnold began to capitalize financially on his power in Philadelphia and engaged in a variety of business deals. Such schemes were not uncommon among American officers at the time.

He lived lavishly in debt and his lifestyle attracted the Continental Congress’s attention. He was brought up on charges and court-martialed in May 1779. He was acquitted of most charges and received a mild reprimand from Washington. Arnold saw the court-martial as a final insult. Arnold wrote to Washington in May 1779, “Having become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet ungrateful returns.”

Many historians debate the reasons for Arnold’s treason. W. D. Wetherell wrote: “Arnold was among the hardest human beings to understand in American history. Did he become a traitor because of all the injustice he suffered, real and imagined, at the hands of the Continental Congress and his jealous fellow generals or because of the constant agony of two battlefield wounds in an already gout-ridden leg? Or from psychological wounds received in his Connecticut childhood when his alcoholic father squandered the family’s fortunes? Or was it a kind of extreme midlife crisis, swerving from radical political beliefs to reactionary ones, a change accelerated by his marriage to the very young, very pretty, very Tory Peggy Shippen?”

Arnold was unhappy with his situation and pessimistic about the country’s future. Arnold predicted “impending ruin” if things did not change soon. Biographer Nathaniel Philbrick argues: “Peggy Shippen exerted a powerful influence on her husband, who is said to have been his own man but who actually was swayed by his staff and certainly by his wife. Peggy came from a loyalist family in Philadelphia; she had many ties to the British. She was the conduit for information to the British.”

Early in May 1779, Arnold started a secret correspondence with Major John André, the British spy chief, sometimes using his wife Peggy as a willing intermediary. This correspondence would lead to Arnold’s change of loyalties. After Washington put him in command of West Point he plotted the fort’s surrender to the British. When his traitorous plans came to light, Arnold escaped.

Arnold was made a general in the British army. He led the attacks which led to the burning of New London and the massacre at Groton’s Fort Griswold. These atrocities were galling to the residents of Connecticut and Arnold became a hated man. Some grudgingly acknowledge that Arnold never set foot in Groton and the massacre resulted from overzealous British troops disobeying Arnold’s explicit orders to observe the conventions of surrender, never the less, the massacre occurred under his command.

So what happened to this brilliant and patriotic man? What made him decide to sell out his country? We know that after Sarasota Arnold was virtually crippled from his injury. The time he spent alone, recuperating from his wounds, in the Albany hospital became the period when the caldron of his resentment boiled over. General Gates, who had relieved him after the first Battle of Saratoga, was mistakenly given credit as the hero of the battle when in it was in fact Arnold’s bold actions that carried the day. Arnold saw himself being passed over for promotion while politically connected lesser officers were promoted.

After his recovery, instead of being given a combat command, he was assigned to the demeaning task of overseeing the occupation of Philadelphia. When he met the beautiful young British spy and his future wife, Peggy Shippen, he was in no condition to resist her influence. Before the honeymoon was over she was already in contact with the British spy Major John Andre. She turned up the heat of Arnold’s dissatisfaction and sense of betrayal. She could play Arnold’s resentment like a violin and he was powerless to resist the music.

With the war ending and word of the British surrender reaching New York Arnold requested leave to go to England with his family, which he did in December 1781. Although paid well for his treachery Arnold was never trusted by the British. He died in London in 1801 at the age of 60.

Legend has it that when he was on his deathbed he said, “Let me die in this old uniform in which I fought my battles. May God forgive me for ever having put on another.” He is buried at St. Mary’s Battersea Parish Church in London. Two flags stand over his tomb, the British Union Jack and a 13-star American flag. His epitaph reads, “Benedict Arnold, sometimes general for His Majesty and sometimes general for the Colonies.” He was a hero and a traitor to the end.