If you ask anyone in Westerly what the town is famous for the answer is probably the beach. In colonial times and up through the 19th-century, the beach was considered almost useless. Its only value was to local farms that harvested seaweed for fertilizer and salt hay for livestock.

Even during the golden age of Watch Hill, the beach was considered too dangerous for swimming. The only reason for downtown Westerly’s location is because the old Pequot Indian trail crossed the Pawcatuck River there. Westerly wasn’t even called Westerly then. It was known as Pawcatuck Bridge up until the mid-1800s.

I decided to find out how the river’s importance to Westerly and the surrounding communities had changed. To get this information I contacted the experts at the Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed Association (WPWA) and set up a meeting with its project director. On a misty day in late January, I drove up to the association’s headquarters overlooking the scenic Wood River. Along the way I passed the remnants of a few hardscrabble farms that once existed here, they are part of the story too.

Before arriving I did some research and found out about the non-profit WPWA. It was started in 1983 in response to great interest in a National Park Service study which identified the Wood and Pawcatuck Rivers “as unique and irreplaceable resources.”

This potentially could lead to designating some of the Pawcatuck River to Wild and Scenic River status. The WPWA has 800 members and over 1,000 volunteers. It has all kinds of great programs including children’s educational programs, water quality monitoring, fish passage projects and development of flood management plans among others.

I parked in a small lot by the ice-covered Wood River. The soft sound of water flowing over the Barberville Dam filled the cold air. Next to a shed filled with colorful kayaks and canoes, I knocked on the door of the main building. Chris Fox, the executive director of the association greeted me and the Project Director Denise Poyer arrived a few minutes later. We sat down and I asked them to tell me what the WPWA was trying to accomplish.

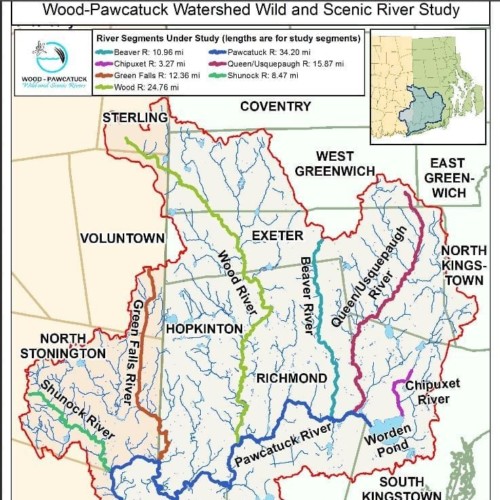

At the moment, their main focus is the Wild and Scenic River initiative. They’re in the third year of a three-year study. The study was authorized by Congress in 2014 with a bill that was passed by the full Congress. The bill appointed the National Park Service to do a three-year study to see if certain rivers in this watershed qualify as natural wild and scenic rivers.

There are a couple of standards of qualification, Poyer said. One is they have to be free flowing and second is they have to have outstandingly remarkable values. The third qualification they want is to make sure that there is community support to take stewardship of these rivers.

“Up until 1980, the only rivers that were designated were big rivers out west that ran through lots of government land. In the east, the National Park Service surveyed several rivers including the Pawcatuck and the Wood River,” Poyer said. “About 20 years ago, they developed a partnership with the Wild and Scenic Rivers Program. They said that if there was a coalition of local communities that wanted to do the stewardship that they would work with them. This has been a much better model for these types of smaller eastern rivers.”

The National Park Service developed a cooperative agreement with the WPWA to conduct and coordinate the study. So the WPWA is two years into this three-year process. 2018 is their final year and their goal is to have the congressional delegates introduce a new bill in Congress that would amend the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to include seven rivers in the Pawcatuck Watershed.

Poyer said that they have identified four major criteria to determine the value of these rivers: cultural, recreational, habitat and geology.

“They have to be what they call ‘outstanding and remarkable’ values,” she said, adding that this is in the wording of the act. “The product that we’re producing is a stewardship plan to protect these values for future generations. This is how this partnership in the Scenic and Wild Rivers Program works. We have to show that not only do we have these values but we already have some protections in place to protect them.”

Another important value is the habitat. The Charlestown Moraine runs from east to west along the coast and what that effectively did was it stop the north-south flow of the river, Poyer said.

“It made it go east and at one point it goes north and then finally flowing south into Little Narragansett Bay,” she said. “So it backed up a lot of water for wetlands. It’s these large wetlands that provide really key habitat for a lot of unique and rare species in the region. So these wetlands are really important.”

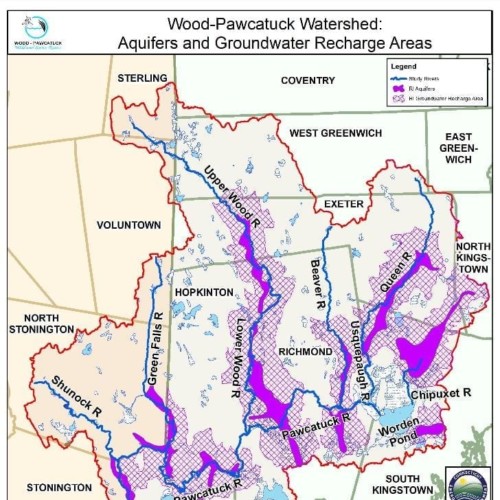

Another important value is the geology which is the extensive aquifers that follow the river courses. As the ice from the glaciers retreated water flowed from the ice creating these river valleys, Poyer said.

“Over time these river valleys filled with sand and gravel which created underground aquifers,” she said, adding that a lot of people depend on these aquifers today. “In Westerly, Stonington, Narragansett and South Kingstown a lot of the town wells are sunk into these aquifers.”

“We identified that culturally we have exemplary historical artifacts in this region because of all the mills that were built here,” Poyer said. “We have great examples of mills, dams, mill villages and a great collection of them throughout the watershed. We also have Native American archeological sites as well. We also found recreationally that we have outstanding kayaking and canoeing, fishing, hiking and other outdoor activities.”

The wild and scenic status is important because the three major things that the status creates is a coalition of local, state and federal agency’s to steward the rivers to make sure that the river’s values continue, Poyer said.

“It creates National Park Service oversight of any big federal projects that might affect the rivers. And it opens up funding to do stewardship projects and perhaps funding for the towns for river projects they might want to do,” she said. “There’s also a PR element. When I get people on this river I introduce it as a future wild and scenic river. How cool is that? This would be the only one in Rhode Island.”

Poyer said that without a doubt, she knows they are going to get the wild and scenic designation.

“I’ve worked in this watershed for 24 years and it is of extreme value to all the people in the region, not just the people in the watershed but all the people in Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut,” she said, adding that they also bring a lot of kids out on these rivers. “We also bring a lot of kids out on these rivers. In fact, I have a program where we bring urban kids out here so that they can see what a clean natural river looks like and take part in healthy outdoor activities.”

Her message to the community: “These rivers are there for everyone. These are our rivers. These are your rivers and we need to protect them. We all have that responsibility to steward these rivers.”