In a previous article, I wrote about the life of Westerly Native and Revolutionary War hero Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel Ward Jr. This next installment is about his role commanding the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, the only black regiment in the Continental Army, and its important role in the Revolutionary War’s Battle of Rhode Island.

The actual Battle of Rhode Island started on August 9, 1778, when 11,000 Continental troops under the command of General Sullivan crossed over to Aquidneck Island in preparation for the attack on the British in Newport. A French fleet was supposed to support the American attack but a hurricane scattered their fleet.

Because of the storm and the departure of the French, the Continental Army’s morale was low and desertion rates were high. The troop had shrunk and after a 12-day siege, a weary and disappointed General Sullivan was forced to withdraw. American deserters informed the British of the withdrawal. Supported by a newly arrived fleet, the British pursued the Americans, hoping to cut off their retreat. General Sullivan withdrew to the northern part of the Island where he set up defensive positions.

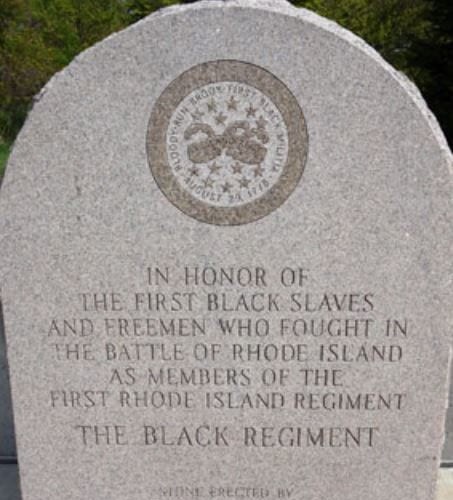

In the battle, Major Ward’s Black Brigade was positioned on the American far right flank to guard the retreat. The brigade was made up of blacks, Native Americans and ex-slaves who had been recruited and trained by Ward.

The British and Hessian troops attacked Ward’s position three times but were driven back. The Hessian commander wrote, “Now we rushed up the hill under heavy fire to take the redoubt. Here we experienced a more obstinate resistance than they expected. They found large bodies of troops behind the works and at its sides, chiefly wild-looking men in their shirt sleeves and among them many Negroes.”

That night, General Sullivan’s army slipped away under cover of darkness. In the confrontation, the Americans lost about 200 men and the British lost 260. Ward wrote after the battle, “Our regiment’s loss was not very great. Several officers fell, and several are badly wounded. I am happy as to have only one captain slightly wounded in the hand. I believe that a couple of the blacks were killed and four or five wounded, but none badly. Previous to this, I should have told you that our Picquets and the light corps engaged their advance, and fought them with bravery.”

By midnight the last of the Continental Army was ferried across to the mainland. According to an account in the New Hampshire Gazette, their retreat was done “in perfect order and safety, not leaving behind the smallest article of provision, camp equipage, or military stores.”

Neither side was able to declare a victory in the Battle of Rhode Island.

If not for a small group of Rhode Island men from the “Black Regiment” standing their ground against a superior force, the Battle of Rhode Island might have been a disaster for the Colonists. General Sullivan wrote, “They repelled the British forces and maintained the field.”