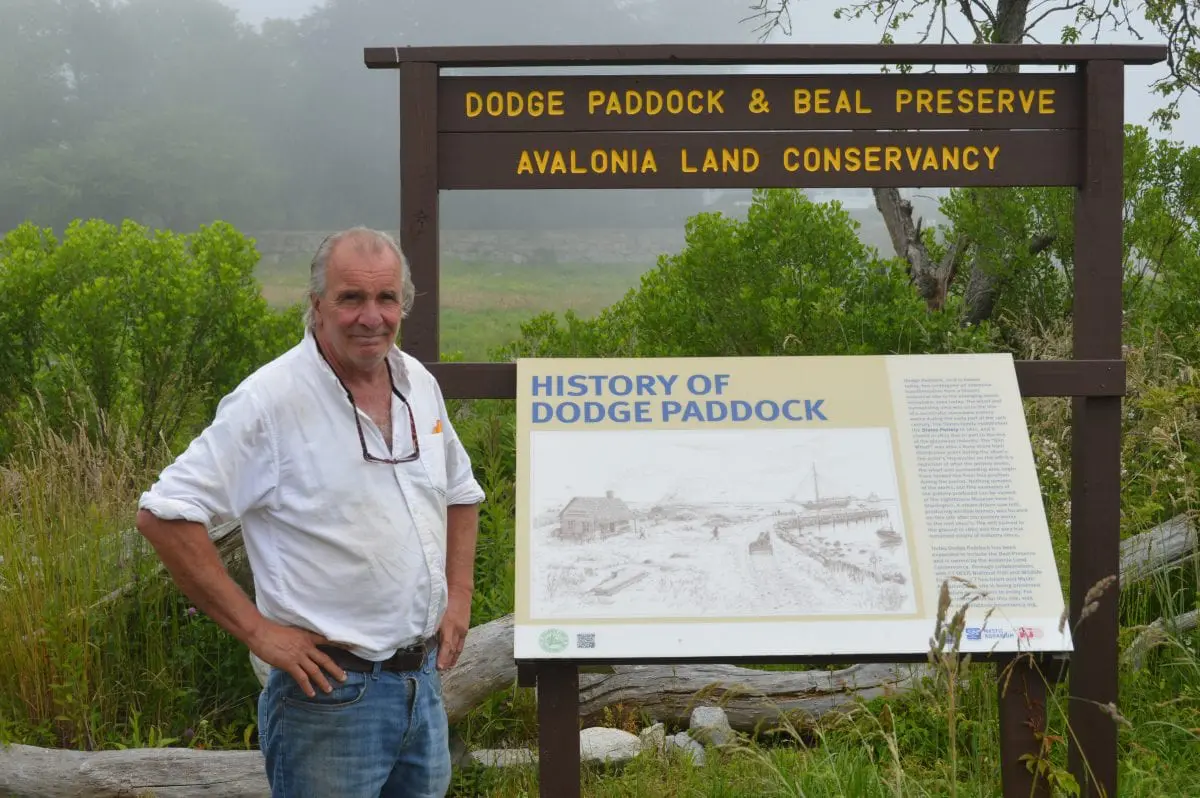

The only sounds are the cries of gulls and breaking waves. Kevin McBride, Ph.D. archeologist and University of Connecticut Associate Professor, is standing at the Dodge Paddock and Beal Preserve in Stonington Borough looking out over what could have been the scene of a battle over 200 years ago. He’s trying to solve the mystery of whether the British tried to land here during the Battle of Stonington.

There are a number of conflicting accounts. Captain Amos Palmer, who fought in the battle, wrote a letter to the secretary of war afterward describing an attempted landing by the British. In that letter, he describes a British barge carrying marines being hit by American cannon fire resulting in a number of British casualties. In the British ship’s logs, there is no mention of this engagement. Did this action ever happen?

The Battle of Stonington was the first American victory on land in the War of 1812. Although mostly forgotten this American victory over a powerful British naval squadron, led by a small group of undisciplined volunteers, leaves many unanswered questions. Why did the British attack an almost defenseless small town of no strategic value? How did a powerful British squadron of warships proceed to lose the battle to a vastly inferior force? The squadron was under the command of Britain’s most illustrious naval war hero, Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy.

The Stonington Historical Society applied for and received a grant in 2018 from the National Park Service’s Battlefield Protection Program to document the battle. Perhaps through the archaeological and historical record, some light might be shed on what actually happened here 200 years ago.

Historians surmise that Hardy chose the town believing it to be a soft target and that would surrender without a fight or that he might have believed the town was the possible source of torpedo attacks on his squadron. 39 years earlier, during the Revolutionary War, another British warship had attacked Stonington. This attack was by the HMS Rose and the British were unsuccessful in that raid.

Perhaps the people of Stonington thought: “we beat them once; we can do it again.” When a British flag was sent with a demand for the town to surrender or be burned magistrate Captain Palmer gave his famous reply, “We shall defend this place to the last extremity; should it be destroyed we shall perish in its ruins.”

There was great consternation in the town when the message was read. Lieutenant Hough, in command of 40 Connecticut militia stationed there, immediately sent a dispatch to General Cushing at New London requesting support. Volunteers started to gather supplies and ammunition and were sent to get the two large and one small cannon where they’d been stored. The cannons were hauled to the hastily constructed Grasshopper Fort, a small 4-foot high breastwork on the harbor side of the point. A small number of men, as few as 20 in number, gathered at the battery with the two 18-pound and one 4-pound cannon. They faced a much larger force of 1,500 British soldiers and sailors, 160 cannons, and five ships. A 16-star battle flag sewn by the women of the Congregational Church was raised over the Grasshopper Fort.

The bomb ship Terror opened fire that night with bombs, carcasses, and rockets. The bombardment continued until midnight. The men of Stonington not at the fort created a fire brigade and were able to extinguish all the fires that the incendiary rockets and bombs started. The following morning the British again opened fire on the town. This was the beginning of a major British offensive. The frigate Pactolus crept up the east side of the point while the brig Dispatch moved straight in to within pistol shot of the shore. The American defenders quickly moved their small 4-pound cannon to the east side and one of the 18-pound cannons to the point to defend against any attempted landing.

On his arrival at the Grasshopper Fort the American hero of the battle, Jeremiah Holmes, saw the Dispatch close to shore. This was his chance to get his revenge against the hated British for impressing him into the Royal Navy. He immediately ordered one of the 18-pounders to be double-loaded. Aiming carefully, using a heavy iron bar to move the gun carriage to where he wanted it, he lit the fuse. The cannon jumped back with a roar, the two shells traveling at over 800 feet a second.

They struck the Dispatch about three seconds later with tremendous impact. The Dispatch was hit many more times and was forced to retire. The Pactolus, with Hardy on board, ran aground and was forced to throw tons of ammunition and supplies overboard to lighten the ship. The British assault had failed.

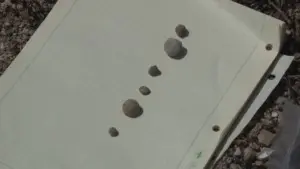

One of Kevin’s volunteers was digging at the Dodge Paddock when the telltale chirp of his metal detector told him there was metal buried in the sand. He was looking for evidence of the battle; musket balls, canister shot, or cannonballs. Usually, the metal objects have nothing to do with the battle and are junk, but not this time. The small object is a musket ball, the fifth ball they’d found that day. Adding these finds to the few dozen balls and a piece of canister shot they’d found last week Kevin believes an engagement did occur here when the British tried to land.

“There are two factors that influenced the British decision to land at this location, first it was out of sight of the main American battery at the point and second, the pier,” said Kevin. “The pier behind me was here at the time of the battle because there was a stoneware factory here. If you wanted to land troops the pier would be the most logical place to do it. Five British barges and launches with marines, canon, and rockets attempted to land on the west side and the east side, and both times they were prevented from doing so by American fire.”

Holding the musket ball Kevin continued, “There are always things you find that weren’t mentioned in the record like the skirmish here in the paddock. Captain Palmer mentioned an exchange of small arms fire and it looks like that’s exactly what we have; a battle line with dropped American and impacted British musket balls and a canister shot. It looks like the British did try to land and perhaps they got off their boats. We have to be cautious. Yes, we have an American skirmish line at the Paddock but were they firing at the boats way out.

“Musket fire is only accurate to 100 yards, that’s about it, so they were pretty close to one another. If you look at the record it says the American’s brought their 4-pounder here and one of the British boats was hit by cannon fire possibly injuring or killing some of the marines on board. That’s when they withdrew. There’s one interesting reference by Captain Palmer in his letter that said the Americans repelled the British with cannon and musket fire. To me that kind of solidifies it – when you find dropped musket balls in a line you’re firing and reloading, that’s an American skirmish line.”

The Battle of Stonington had little strategic importance in the war but none the less was a great boost to American morale. The research being conducted under the battlefield grant has revealed that although the Americans certainly won the battle the British also declared it a success. In a letter from Commander Hardy to his commander, Admiral Hotham, Hardy described how they shelled the town and caused much damage. The official British attitude was, good: “we taught them a lesson.”

As far as the mystery surrounding the British attempted landings, Kevin is determined to find an answer. “It would be worth coming back to this field. We couldn’t survey it as well as we wanted to because the vegetation was too high. Once you start lifting a metal detector off the ground only a few inches you lose that depth. So I think our plan is to wait until the fall, when they cut it and come back to see if that battle line is real. I think it’s real.”