It was Friday, August 30, 1872, and the end of another idyllic summer in Watch Hill. The Ocean House and the other large hotels were still full of guests. The weather the past week of August had been perfect but early that fateful morning, while the guests were still sleeping, the weather changed. Squalls and a cold rain was driven by a strong southeast gale rattled the windows. The sound of huge breakers boomed on the beach.

As guests and hotel employees woke up and looked to the surf they were horrified to see human forms struggling in the water. The people caught in the heavy surf were passengers from the Steamship Metis which had sunk hours earlier five miles offshore. Hotel employees ran to spread the alarm.

As the Metis prepared to leave New York she was hastily loaded with a cargo of cotton bales. The large heavy bales were stowed on top of some of the hatches. These hatches gave access to the holds of the ship and this unsafe loading would later have unforeseen consequences.

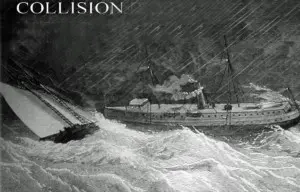

The Metis left New York City under the command of Captain Charles L. Burton around 5 p.m. on August 29 for the 12 to 15-hour trip. She headed through Hell Gate into Long Island Sound with her sister ship Nereus following a mile astern. During the night as the two ships steamed up the Sound the weather changed to a strong gale with high winds, heavy seas, and pelting rain.

At 3 a.m. the lookout on the Metis saw the signal from the Watch Hill Lighthouse. The Metis was making about 12 knots when through the driving rain the lookout saw another vessel approaching less than 150 yards away. The approaching vessel was the schooner Nettie Cushing.

The 91 ton Nettie Cushing, under the command of Captain Emory D. Jamison, was sailing in the opposite direction bound from Maine to New York City with a cargo of lime.

We were steering clear when three minutes after, just as she reached us, she gave a sheer across our bows and struck on the starboard side of our stem, tearing away our bowsprit and headgear close up to the knightheads. Although the weather was thick our lights were burning brightly at the time and so were the steamers. We swung clear and I shouted to her that we were sinking but she paid no attention but kept on. Subsequently, I heard her blowing her whistle.”

The captain of the Cushing did not know what vessel they’d struck and assumed the strange steamer that had appeared out of the storm only minutes earlier had not been seriously damaged. The Nettie Cushing was leaking badly and Captain Jamison thought his ship would sink. He had no choice but to try and proceed to the nearest port which was New London. The Cushing arrived at the mouth of the Thames River at dawn barely afloat.

On board the Metis, Captain Burton ordered the engines stopped and two of his officers to look for any damage. Aside from some rigging that had come through a porthole in the crew’s quarters, everything else appeared normal. The two officers then tried to examine the forward cargo hold where the heavy cotton bales had been stowed on top of the hatch. They reported that it would take two to three hours to remove the cargo to gain access. The officers then took a lantern and leaning over the side of the ship, inspected the hull for damage and couldn’t see any. After sounding the hold and finding no water they reported to the captain that they could find no critical damage.

Believing that all was well, Captain Burton restarted the engines and reversed course to see if the schooner required aid but the schooner had already left. The Nereus came alongside the Metis and signaled to see if Burton needed assistance. Captain Burton signaled the Nereus that all was well.

The Nereus’s captain, assuming all was well, resumed his course and steamed off out of sight. Why the Nereus did not stand by to make sure the Metis was alright is one of the mysteries of this tragedy. Captain Burton brought the ship around and resumed her course to Providence.

Although little damage was apparent on deck, unbeknownst to Captain Burton, the hull near the bow of the Metis had been penetrated. Tons of water was rushing into the forward hold but was held back by an old wooden bulkhead. Later in the investigation into the tragedy, it was found that 3-foot holes had previously been cut into that bulkhead and later closed up. These had weakened the bulkhead and as pressure built up it gave way suddenly.

This explains why no water was found earlier when the officers examined the hold. At 4:30 a.m. the engineer sent word to Captain Burton that water was flooding into the engine room. He told the captain that they were sinking and should try and beach her.

The captain turned the Metis toward the Watch Hill shore but after a mile, the water reached the boilers and the fires went out. With no power or pumps, the Metis was doomed. Only 30 minutes later at 5 a.m. the Metis sank beneath the waves.

The sleeping passengers that had been awakened by the collision rushed on deck. Many were still in nothing but their nightclothes and in the dark stormy night, terror and confusion reigned. With heavy seas breaking over the ship the purser and engineer tried to help passengers find life preservers but there were not enough to go around.

The engineer tried to lower lifeboats but was hampered by the heavy seas. According to eyewitnesses, Captain Burton made no attempt to help the passengers. When four lifeboats were launched they were mostly filled with crew members. As the ship sank bales of cotton and other freight broke loose and floated away. Some of the passengers jumped into the sea after them only to be carried away by the storm.

There are many tragic tales from that fateful night. Among the saddest was the story of a young family of four. They, like most of the passengers, were asleep when the collision occurred but were awakened by the shock of the collision. Almost immediately a steward rushed into their stateroom informing them the ship was sinking and to put on their life preservers. They woke the children, one a baby only six weeks old, the other, a boy three years old. The mother took the infant and the father took the three-year-old and they made their way up to the deck.

The water was knee deep already and within five minutes the couple was washed into the sea. In the pitch black night the storm waves swept the children from their arms. The husband was now exhausted by the struggle and slipped beneath the waves. The woman was saved just in time by the Revenue Cutter Moccasin.

Over 50 passengers climbed to the top of the hurricane deck waiting for the ship to sink. Miraculously as the Metis foundered the hurricane deck became detached and floated away with desperate passengers clinging to it. Captain Burton was one of the 50 who rode the makeshift life raft toward shore and survived.

The storm continued to rage as the 50 or so desperate and terrified passengers clung to the hurricane deck of the Metis which had become a giant life raft. As morning dawned the Watch Hill shore became visible and a few hours later the hurricane deck reached the breakers below the Ocean House. The heavy surf broke over the deck washing people into the debris-filled water. The dramatic rescue of the survivors will follow in part 2 of this story.