Read the Metis Disaster part 1 and part 2 first.

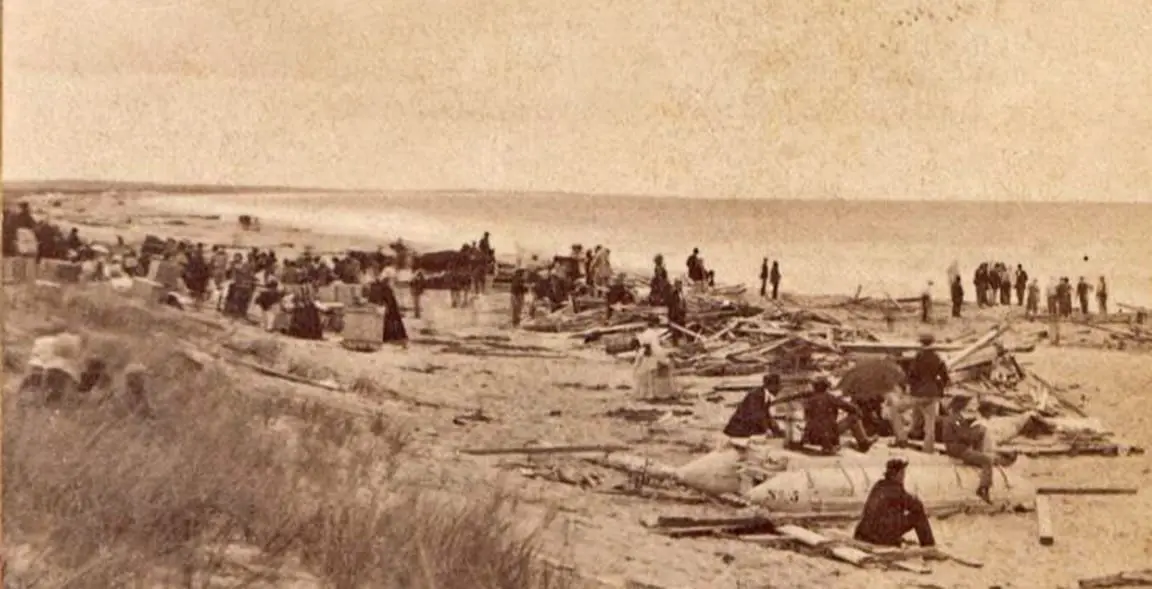

As news of the wreck spread that weekend, a large crowd of onlookers lined East Beach in Watch Hill for miles. The surf was still running high washing wreckage from the Metis up onto the beach and burying it in the sand. Looking for treasure, men using shovels recovered barrels, boxes, and bales of cotton.

Two of the Metis’ life boats and a life raft had been pulled up on the beach. The large smokestack from the ship was lying half buried in the sand. This large metal pipe had protruded through the hurricane deck into the water during the storm and acted as ballast, keeping the deck from capsizing in the heavy seas.

A correspondent from a local paper wrote, “It was evident that in only a few hours all signs of the great disaster will disappear. We were told that the last four bodies to come ashore at Watch Hill were identified, had been removed; and that only two injured persons rescued from the wreck remained at the hotels.” Many of the dead had been taken to a hall in Stonington where those searching for missing loved ones, as well as curiosity seekers, walked past the unidentified bodies.

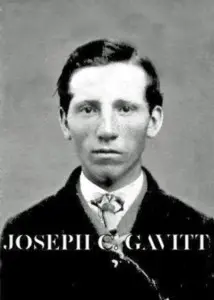

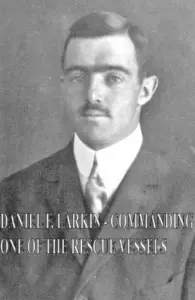

Receiving the medals were Capt. Jared Crandall, Albert Crandall, Daniel F. Larkin, Frank Larkin, Byron Green, John Harvey, J. Cortland Gavitt, Eugene A. Nash, Edwin Nash, and William Nash.

A letter accompanying the medals read, “Sir: I have the honor, by direction of the President to transmit to you the medal authorized by the joint resolution of Congress, approved Febuary 24, 1873, to be made and presented to you as one of the gallant company of ten, belonging to the town of Westerly, Rhode Island, who on the thirty-first day of August, 1872, at the imminent peril of their own lives, rescued from drowning thirty-two persons, on the occasion of the wreck of the Steamship Metis, on the waters of Long Island Sound. In sending you this medal, President Grant desires that it be accompanied by the glad expression of his recognition of the courageous and humane conduct of which it is the memorial. I have the honor to be, Sir, your obedient servant, B.H. Burton, Secretary.”

The medals were solid gold and worth $140, a large sum at the time. The Boston jeweler that made the watches was dishonest, he imitated the faces of the medals in a cheap watch case and sold the gold for its weight. Gavitt lamented his foolish decision and tried for years to recover the medal but was never was able to. “Oh, what a fool I was to part with it.”

Gavitt also received a medal from a private party which he melted down and made into two spoons. His niece, Jennie Langworthy, put them on display in Westerly for many years. The spoon pictured a man in a boat by the lighthouse pointing out to sea and the inscription read, “Steamer Metis, August 31, 1872.”

During the official investigation by the Steamship Investigation Service each captain blamed the other for the collision and claimed that their ship had the right of way. Captain Burton and his pilots were cited for failure to avoid a collision and inefficient management of the aftermath. Only six months later, Captain Burton was back in command of a vessel on the same route the Metis had taken when it went down.

One positive outcome of the disaster was the construction, in 1879, of an official U.S. Life Saving Service Station at the Watch Hill Light.

A year after the Metis disaster, Gavitt joined the newly formed Westerly Police Department. Gavitt had a restless and adventurous spirit and only two years after joining the department left to become a conductor on the Providence and Pawtucket Horse Railroad. He soon tired of that and decided to go to sea. In 1877 he headed to New Bedford where he and his friend, Edwin D. Schofield, signed on the whaleship Mabel. After the ship arrived in Hobart, Tasmania in 1880 Gavitt decided to stay in Tasmania.

It’s not clear why he made the decision to stay, perhaps it was just his restless spirit or perhaps the memory of the great disaster still haunted him. He joined the Hobart Police Department as a constable and in 1877 was promoted to detective sergeant. In 1894 he was granted a Certificate of Naturalization and became a citizen of Tasmania.

The wreck of the Metis was the greatest maritime disaster in Rhode Island history. It was known as the great disaster until 35 years later on February 11, 1907, in almost the same place, the steamer Larchmont collided with the schooner Harry P. Knowlton. There were as many as 150 passengers on board the Larchmont and because of the extreme cold there were only 17 survivors now making this Rhode Island’s greatest maritime disaster.

There were many similarities between the two shipwrecks. Both steamers collided with schooners in storms and both were under the command of junior officers when the collisions occurred. The collisions occurred only miles apart and both accidents might have been caused by the two steamships helmsmen. Both helmsmen either panicked or were given the wrong orders, in each case turning their vessels in the wrong direction, right into the path of the oncoming schooners. The schooners, being under sail, couldn’t easily alter course and would’ve had the right of way. In both shipwrecks, the exact number of dead was never determined.

Today, the wreck of the Metis is a popular dive site three and a half miles from the Watch Hill Lighthouse in 130 feet of water. The wooden hull has rotted away and only the engine, the boiler, and the driveshaft are still visible marking the place where 147 years ago one of Rhode Island’s greatest disasters unfolded.