The weather in New England has always been fickle, even the weatherman often gets it wrong, sometimes really wrong. I remember a winter when the Channel 10 weatherman predicted that we would get a dusting to an inch of snow. The next morning we awoke to over 20 inches and because Mastuxet Road where we lived was a side street we didn’t get plowed out for three days. Although this was a lot of snow it wasn’t a real blizzard. Maybe that’s why people in New England take what the weatherman says with a bit of skepticism.

The definition of a blizzard can get fuzzy because a storm can be considered a blizzard in one location but not in another, let me explain. Officially, the National Weather Service defines a blizzard as a storm which contains large amounts of snow or blowing snow with winds in excess of 35 mph and visibilities of less than 1/4 mile for an extended period of time (at least three hours). Here in southern New England, we get a storm that meets those criteria every other year but they are not blizzards.

What I mean by a real blizzard is a major storm that causes significant loss of life and widespread disruption. The term blizzard came from an Iowa newspaper in 1870 to describe a snowstorm. Previously the term blizzard referred to a cannon shot or a volley of musket fire. By the 1880s the use of the word blizzard was widely used by many across the United States and in England.

There are two rating scales used by The National Weather Service to measure winter storms and their intensity. The first is the regional snowfall index or RSI.

The RSI is a system used to assess the societal impact of winter storms in the six easternmost regions of the US. Storms are ranked from category 1 to 5 on the scale with 1 being classified as Notable and 5 as Extreme. Out of the over 500 historical storms assessed since 1900 only seventeen storms have been given a category 5 ranking.

The other scale used to measure winter storm intensity is the Northeast Snowfall Impact Scale or NESIS. The NESIS is a scale used to categorize winter storms only in the northeast region and it has 70 storms on its list.

I have a major issue with both of these scales because if you look at the storms they list some are on one scale but not the other and the Blizzard of 1978 doesn’t even show up in the RSI index and is ranked 14th in the NESIS scale.

The reason for the lack of uniformity in the scales is that storms may affect some areas severely and other areas hardly at all. What would be a major storm in New York might just be just a nuisance in Rhode Island.

I’ve made my list; maybe you have your own. There are seven storms on my list which meet the criteria for extreme that have occurred in southern New England. They are The Great Snow of 1717, The Blizzard of 1888, the 1969 100 Hour Storm, The Blizzard of 1978, the 1993 Storm of the Century, the 1997 April Fools Storm, and the February 2013 nor’easter.

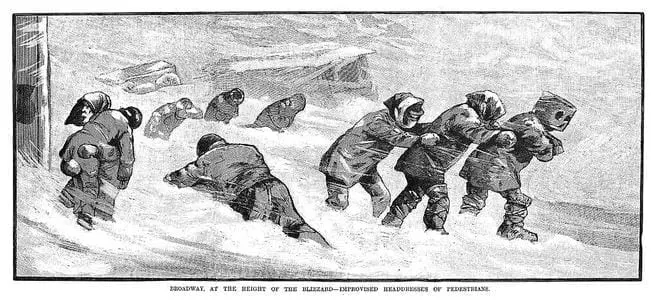

The greatest blizzard to ever hit New England started on Sunday, March 11, 1888, and intensified the next day. The storm, referred to as the Great White Hurricane, paralyzed the East Coast from the Chesapeake Bay to Maine. The U.S. Army Signal Corps in Washington predicted: “fresh to brisk winds, with rain, will prevail, followed by colder brisk westerly winds and fair weather throughout the Atlantic states”. This forecast was very wrong.

On Sunday afternoon in New York City, the rain came and the temperature slowly began to drop. It reached freezing just after midnight and fell to 6 degrees the next morning. The rain turned to snow. The wind speed rose with gusts of up to 80 mph. By Monday morning everything in New York City was in chaos.

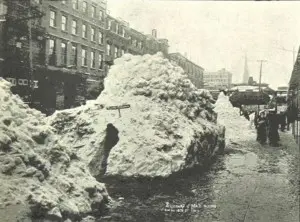

The National Weather Service estimated this nor’easter dumped as much as 50 inches of snow in parts of Connecticut and Massachusetts while parts of New Jersey and New York had up to 40 inches. Drifts were reported to average 30–40 feet and covered the tops of houses from New York to New England.

The highest drift of 52 feet was recorded in Gravesend, New York. From the Chesapeake Bay through New England, more than 200 ships were either grounded or wrecked resulting in the deaths of at least 100 seamen. More than 400 people died from the storm and the ensuing cold including 200 in New York City alone.

Although the Blizzard of 1888 was the worst storm to hit all of New England the Blizzard of 1978 will probably go down as Rhode Island’s worst winter storm. The “Blizzard of 78” formed on Sunday, February 5, and lasted for two days. The storm’s power was made apparent by its sustained hurricane-force winds of approximately 86 mph with gusts to 111 mph and the formation of an eye in its center like a hurricane.

While a typical nor’easter brings steady snow for six to 12 hours, the Blizzard of 78 brought heavy snow for an unprecedented full 33 hours. Rhode Island was at the epicenter of the storm with snowfall totals breaking a record of 27.6 inches in Providence and 40 inches in many outlying areas.

The storm killed about 100 people in the Northeast and injured about 4,500. It caused more than 1.91 billion in damages in 2017 dollars. Just like the blizzard of 1888 the forecast was totally wrong.

The first forecast Sunday night predicted only six inches of snow and most schools and businesses planned to open but by eleven o’clock on Monday, February 6, the National Weather Service put out an ominous warning.

Office workers all over the area were dismissed early hoping to beat the storm but it was too late. Although Governor J. Joseph Garrahy had ordered an emergency evacuation of all public buildings shortly before noon too many people had lagged and became stuck in the storm.

In Massachusetts and Rhode Island at least 3650 cars were stranded and Route 95 was turned into a giant frozen parking lot, many did not make it home for several days. Fourteen people died on I-95 near Boston because snow prevented exhaust fumes from escaping their idling vehicles. I-95 eventually had to be evacuated by cross-country skiers and snowmobilers.

Other transportation links were disrupted and shut down throughout the region stranding public-transit commuters in city centers. Many people were left without heat, water, food, and electricity for over a week after the storm was over. Approximately 10,000 people moved into emergency shelters. Some 2,500 houses were reported as seriously damaged or destroyed.

Several people were found dead in downtown Providence near the central police station, they may have been seeking shelter. Ten-year-old Peter Gosselin, of Massachusetts, disappeared in the deep snow just feet from his home’s front door and was not found until three weeks later.

At the harbor in Salem Massachusetts, the Greek oil tanker Good Hope had issued a mayday call for help. Receiving word of the tanker’s troubles decorated Captain Frank Quirk and his crew boarded the 42-foot Coast Guard boat “Can Do” to head out into the storm in an ill-fated rescue attempt.

The “Can Do” was buffeted by winds of up to 110 miles per hour and smashed by huge seas. The seas broke the windshield flooding the electronics and killing the engine. The crew deployed the anchor. At 3:30 AM the last radio transmission from Captain Quirk came in:

“Will hold on. Sure wish we could raise some power. It’s really hopping out here, but we’re making it”, they didn’t.

All 5 crew members were eventually lost. There were many other tragic deaths in this great storm. Finally, after 33 hours of continuous snowfall, the skies of New England began to clear and the greatest winter storm since the blizzard of 88 was over.

This morning I just finished watching the weather on TV and The National Weather Service has issued a winter weather advisory for six inches of snow along coastal Rhode Island, exactly the same forecast predicted the day before the Blizzard of 78. Let me see, I better check to make sure I have bread, milk, batteries, and maybe some hot toddy makings just in case!